Anne Speier

Wild

Boltenstern.Raum

May 3rd 2017 – Jun 1st 2017

Exhibition Text

“I find it harder and harder everyday to live up to my blue china.”

– Oscar Wilde

“The ideal fusion of the useful and the beautiful found in these French ceramics is the essence of what inspired MaryLou Boone to assemble her outstanding collection from the foremost manufactories of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Originally made to emulate Asian hard-paste porcelain imported into Europe, faience and soft-paste porcelain ultimately became distinctive and sought-after ceramics in their own right. The collection includes wares for dining and taking tea, for storing toiletries, and for preparing mixtures that comforted in time of sickness. These objects emphasize myriad aesthetic influences, chronicle advances in technology, and reflect the rhythms of domestic life, providing a unique view of French customs and culture.”

-Marylou Boone collection exhibition text LACMA, 2013

As an aestheticist, Oscar Wilde in his quote above could be referring to the importance of the beauty of things, and how that can, in and of itself, be enough. Extended further, for him perhaps any attempt to validate these aesthetics politically or apply overarching meaning to them might seem hopeless, if not ridiculous.

The image on the invitation, and the above mentioned quote is taken from an exhibition of Marylou Boone collection that was on display at LACMA in 2013. The collection on display was comprised mainly of French porcelain from the 17th and 18th century, and although produced in France, the pieces incorporated stylistic aesthetics originating in Chinese blue porcelain from the Ming Dynasty. The crucial aspect here is how smoothly these ‘foreign’ or ‘exotic’ traditions were integrated into French cultural production, and the lightness, at least retroactively, with which we remember these subsequent transitions of aesthetics and styles, perhaps neglecting the historical significance of this cross-cultural development and stylistic merging.

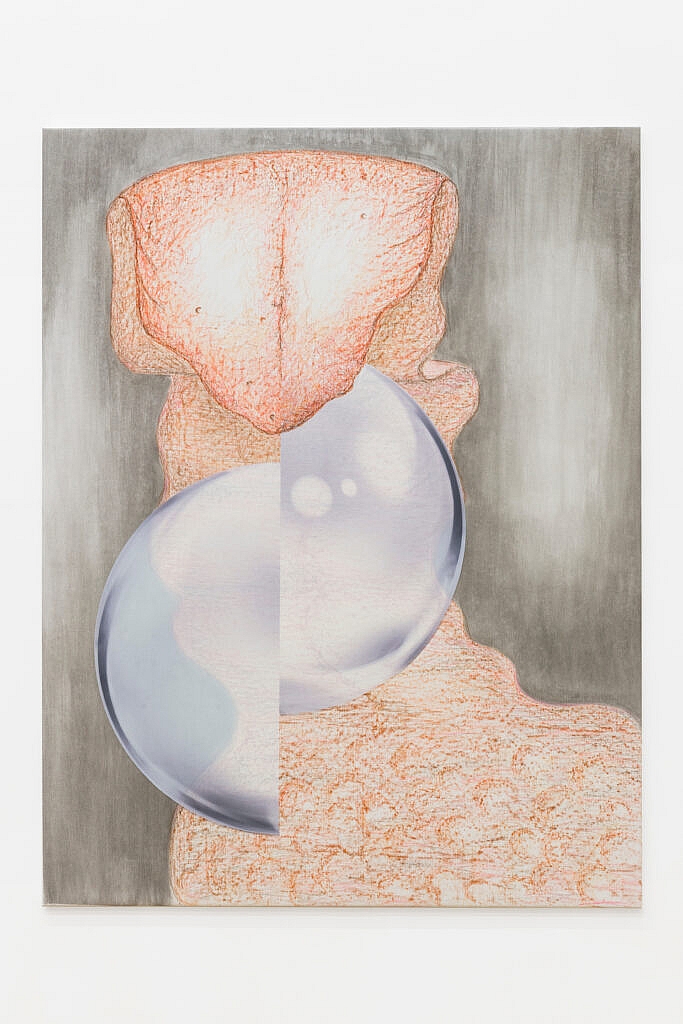

The imagery used in auction house catalogues or the archival inventories of collections often presents singular objects floating in darkened spaces, as such they lack any pictorial reference to the outside world. These images, as if like Wilde provoked, present beauty as a self-contained characteristic, without mimesis to a cultural moment. As a singular object of beauty, a vase formally then extends this isolation; it is a vessel that might be filled with something, or a shell, or a protective shield, and in its shape is almost a closed bubble. Yet they are simultaneously extremely delicate objects that can break easily and made of an almost transparent material. Metaphorically, the vase cum bubble as a protective entity, mirrors the contemporary moment, and lays claim to the absurdity of the myth that it is the maintenance of the bubble itself that keeps intruders and therefore the assumed danger away. While even if the people inside the bubble; like the orangutan hanging; like the photographed blue china in the auction catalogue; are in a perceived state of isolation, under a globalized condition of international dependency and exchange, all actors are as much involved in current affairs, as those on the other side.